You are here

Hey Look Me Over: The Films of Pat Rocco

About the Author

Whitney Strub is associate professor in the History Department and director of the Women’s & Gender Studies Program at Rutgers University-Newark. He is author of Perversion for Profit: The Politics of Pornography and the Rise of the New Right (2011) and Obscenity Rules: Roth v. United States and the Long Struggle over Sexual Expression (2013), and co-editor of Porno Chic and the Sex Wars: American Sexual Representation in the 1970s (2016). His work has appeared in American Quarterly, Journal of the History of Sexuality, Journal of Women’s History, Journal of Social History, Radical History Review, QED, Slate, Salon, Vice, OutHistory and elsewhere. He co-directs the Queer Newark Oral History Project, and blogs at strublog.wordpress.com.

When Pat Rocco arrived at the Meat Market in early 1970, so too did the police. Rocco was at the gay nightclub (in El Segundo, near Los Angeles International Airport) to film a nude dance; the cops were there to harass patrons and arrest the owner. So Rocco simply shot the scene as it occurred: a plainclothes officer roaming the bar, checking IDs, the owner being hauled out. It’s easy to miss the profound importance of the resulting short, Meat Market Arrest; the whole event plays out with the quality of a weary routine, and the ever-affable, even-keeled Rocco narrates live and onscreen, no firebrand: “I think it’s another example of what might be considered by some people, and I think I would venture to say certainly my own opinion, a form of police harassment.”

In fact, Rocco had captured the daily texture of the homophobic police state that was the United States well into the 1970s, live on camera, in a way no other filmmaker had.1 Meat Market Arrest is singular in its visual documentation of the casual terrorization of queer people that was standard operating procedure for police around the nation. It doesn’t look like terror, because most everyone involved is used to it; at the same time, this is a population criminalized simply on account of their identities. “The Whole World is Watching,” went a popular New Left slogan of the time, often chanted against violent authorities—but even the ostensibly progressive New Left remained enmeshed in homophobic attitudes at the time. Rocco neither looks nor sounds like an angry radical, but even in 2013 it can be a courageous act to point a camera at a cop, much less in a gay bar forty years ago. Because he did point and shoot, we have this unique filmic record.

Meat Market Arrest (1970)

If Meat Market Arrest points toward Pat Rocco’s importance as a gay documentarian, it doesn’t end there. Three days later, he returned to the bar to finally capture the nude dance. In the film’s second half, he chats with lawyer Walter Culpepper and dancer Bob Philpot about the pending cases, then lets Philpot perform, a sweet, mellow, fully nude dance—to be shown to a judge, in fact, in an effort to establish the artistic merit of the Meat Market’s dancers. Here we see Rocco’s other side: the groundbreaking erotic filmmaker whose joyful celebrations of gay eros boldly appeared at the Park Theatre in downtown Los Angeles in the summer of 1968, a year before Stonewall, and reveled in nude men carousing, running, jumping, kissing, and cavorting, all at a time when homosexual activity remained illegal even in the state of California. In some ways, Meat Market Arrest is the key to Rocco’s entire expansive oeuvre, linking his twin cinematic imperatives through its insistent documentation of gay life and celebration of gay desire, even in the face of attempted suppression.

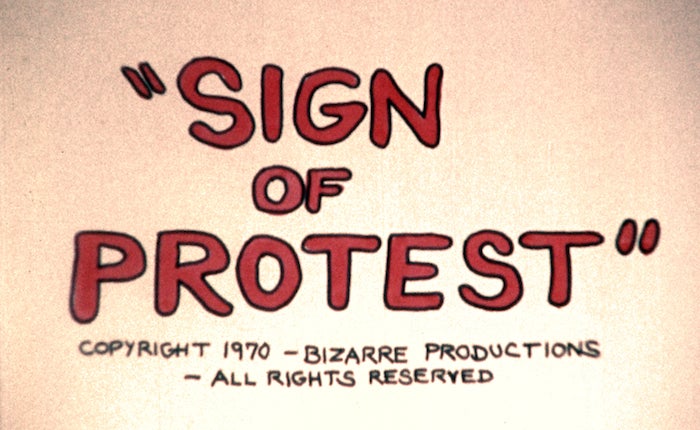

Rocco was a pioneering figure in the cultural wing of the sexual revolution, but his work goes too little remembered today. He tends to pop up in cameo appearances in various gay histories, but his rich and varied film work has received far too little sustained attention.2 Though on a technical level he was no cinematic virtuoso, between 1968 and 1976 Rocco built a truly remarkable body of work. His erotic shorts helped spearhead the zesty vitality of gay liberation (not to mention paving the way for such hardcore icons as Wakefield Poole and fellow Angeleno Fred Halsted)—which his documentaries in turn captured, in styles that ranged from the cinema vérité of Sign of Protest (1970), in which gay activists demand the removal of an ineptly misspelled “Fagots Keep Out” sign at Barney’s Beanery in West Hollywood, to the colorfully playful We Were There (1976), which features naked gay men, lesbians, and elephants all triumphantly marching in Gay Pride Week.

Meat Market Arrest (1970)

Born Pasquale Vincent Serrapica to an extended Brooklyn Italian-American family in 1934, Rocco took his stage name only later, as he navigated the entertainment industry after his family moved to Southern California during his childhood. Rocco’s personal papers, at the ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives, chart his ambitious course: from singing devotional music in the mid-1950s, to a contract with Hal Roach Studios and a television gig on the Tennessee Ernie Ford Show; from a movie theater he ran in the Simi Valley in the early Sixties, through directing plays at mid-decade. Through these experiences, he learned not only showmanship, but also the internal structural operations of the industry—both of which would pay off later.3

Rocco had never resided in what was quickly becoming labeled by the late 1960s as “the closet”; sexually active as a teenager, he had been forced to finish high school through distance learning with a tutor after refusing to deny his homosexuality. When he saw an ad in 1967 calling for physique photographers, he gave it a shot; where predecessors such as Bob Mizer of Physique Pictorial had been forced to coat their homoerotic images in thin alibis of non-sexualized bodybuilding, Rocco’s generation rejected such subterfuges (which were necessary in 1950s America, to be sure—even without openly admitting his magazine’s gay erotic charge Mizer was repeatedly arrested). Clark Polak, the Philadelphia publisher of Drum, had begun defiantly publishing openly gay full-frontal nude images in 1965, joined shortly by enterprising firms like Minneapolis’s DSI.4 Rocco followed suit.

Sign of Protest (1970)

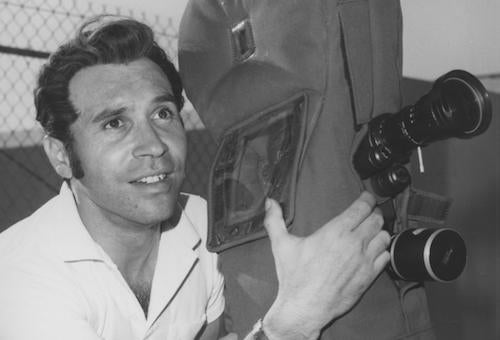

Rocco’s photographs sold well, and on something of a whim he began bringing an 8mm film camera to his shoots. The timing could not have been better: a confluence of forces, including gay activism and its push for increased visibility, the rapidly diminishing scope of obscenity laws (historically disproportionately aimed at queer expression), the market demands of a gay consumer base, and the broader spirit of sexual revolution, all worked in tandem to open a new space for gay erotic expression. He entered gay film history not as an activist, nor through the queer underground of Warhol, Anger, or Kuchar (“I didn’t know there was a gay avant-garde,” he today recalls). Instead, he belonged to a history of gay entrepreneurship, which the historian David Johnson has recently argued played a formative role in modern gay politics.5 Rocco capitalized on his own good looks, appearing shirtless with a camera in the catalogs for his Bizarre Productions—which also emphasized positivity, declaring, “we are especially proud of the movies offered here.”6

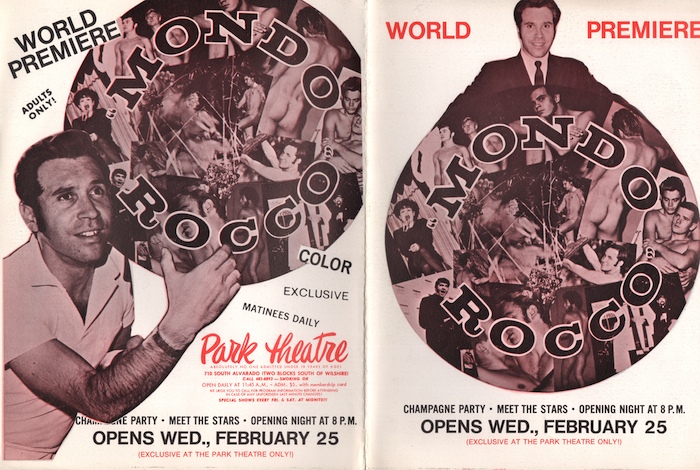

Gay erotica long preceded 1968, of course—but as a private, underground, or black-market activity. Thanks to such archives as the Kinsey Institute, the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco, and Cornell University’s Human Sexuality Collection (among many others), not to mention two generations of historians too numerous to mention, we now have access to personal hardcore photograph collections dating back to the 19th century, handwritten and mimeographed smut stories passed around as samizdat literature in a homophobic society, and “physique” movies of barely-clad men posing, wrestling, and occasionally coming just to the brink of overtly romantic expressions. But when Pat Rocco’s micro-budgeted films premiered at the Park Theater in the summer of 1968, billed as part of “the first homosexual film festival,” they broke new ground.7 So uncertain was the terrain that Rocco and the theater kept a lawyer on site, very conscious that arrests might interrupt the screening.

Sign of Protest (1970)

Formally and technically, Rocco’s early films remained simple, focused primarily on naked male bodies. Magic in the Raw (1968) is paradigmatic: a five-minute short featuring a magician bringing into being a sexy cowboy, undressing him with each wave of a wand, then accidentally making his creation disappear with a misplaced tap. The jump cuts that remove each item of clothing are imported directly from the 1890s—indeed, other early shorts such as Up, Up, and a-Wow (1968), featuring four minutes of naked tree-climbing, hearken back to Eadward Muybridge’s early motion studies, while The Gang That Couldn’t Go Straight (also 1968) utilizes silent slapstick humor in its chase scene that moves from foot to bike to pogo stick—naked, of course. But while the stylistic tropes looked backward, the playful, irreverent eroticism was very much a product of the late Sixties, a bold gay self-assertion no less political for being funny and slightly clumsy.

Rocco showed experimental ambitions at times; The Boy, the Forest, the Dream (1968) begins with handwritten credits flashing in semi-psychedelic red, and after a pastoral striptease by Ted Huston in the streams and trails of Los Angeles National Forest’s Mount Baldy, Rocco swerves to a jarring, Brakhagian dream sequence of pulsing, jerking camera moves and cuts. He flirted with darker existential themes at times, particularly in his films written by star Joe Adair, who plays an isolated, alienated hustler in A Matter of Life (1968) and Rocco’s first feature-length narrative film, Someone (1968, again—truly an expansive body of work he generated this year alone!). The latter film shows how rapidly Rocco’s ambitions expanded, and though it’s largely forgotten today, its bisexual ambivalence and unglamorous L.A. location shooting (more anticipatory of Jacques Demy’s Model Shop or Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point than reflective of, say, Beach Blanket Bingo) make it a fascinating historical relic. Rocco even won praise from Variety, which acknowledged his “sensitive filmmaking talent” with the style “of a romanticist, not a pornographer.”8

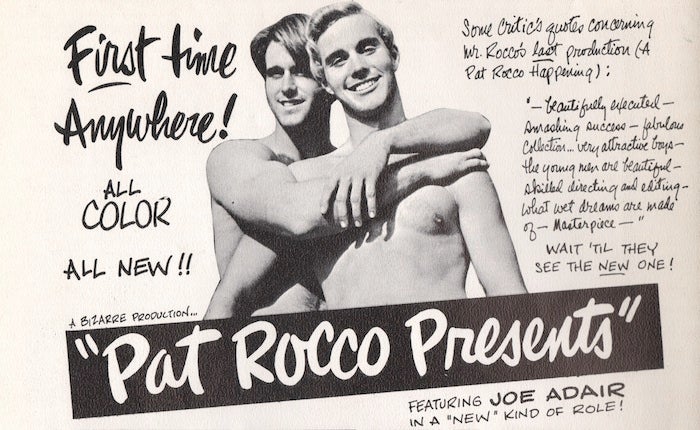

Promotional material for the Park Theatre. Image courtesy of Pat Rocco.

His primary media base, however, was the gay press. From the start, Rocco’s films won consistent adulation there, as typified by Jim Kepner’s early-1969 rave review in the homophile magazine Tangents. Contrasting Rocco against the “awkward, backyard cock-danglers” of the “old physique photographers,” not to mention “Anger’s old pathologicals” and “Warhol’s posturings,” longtime activist and journalist Kepner saw in Rocco “something homosexuals had never before found on the screen”: “lyric and romantic depictions of male love and beauty, unmorbid and frankly physical, without the smirking leer.” He found it “exhilarating, fresh, ideal, basic, and agonizingly beautiful.”9 As Rocco rolled out one successful set of shorts after another from 1968 to 1970, gay audiences clearly agreed. Success emboldened Rocco, and his films grew more adventurous on multiple fronts. While his initial shorts had featured abundant full-frontal male nudity, overt sexual content remained circumscribed by the threat of obscenity charges. Yet already by the end of 1968, A Very Special Friend depicted two attractive young men cruising one another across Los Angeles, culminating in intense kissing and full-body naked contact as they rolled around Griffith Park. Though very much softcore, this was a step toward more graphic sexual content than publicly-screened gay erotica had yet dared attempt—indeed, a 1969 set of shorts screened as Pat Rocco Dares.

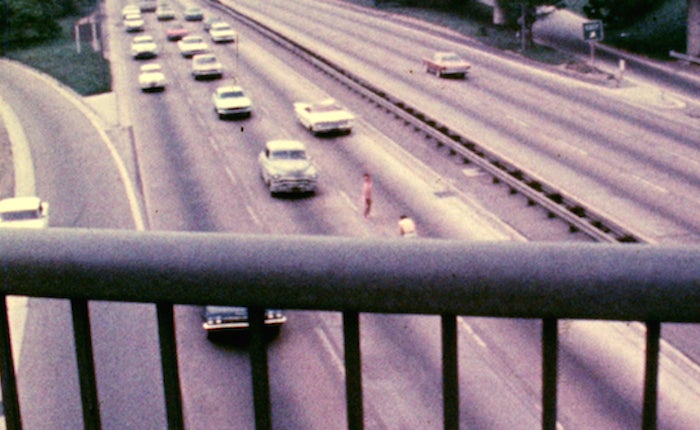

From the start, Rocco had employed courageous guerilla shooting, capturing remarkable footage of Hollywood Boulevard, Griffith Park, Echo Park, Los Feliz, and other hotspots of gay L.A. geography; above and beyond his significance as a gay filmmaker, he merits greater recognition as a Los Angeles filmmaker. In A Breath of Love (1969), he undertook the astonishing feat of filming a naked man (Brian Reynolds) dancing in the L.A. Freeway. Rocco and friends blocked the heavily-trafficked road by deliberately clogging it behind the shoot—as he then documented in the extraordinary How to Shoot a Nude on the Freeway (1969), which shows Rocco and crew returning for a second take after they forgot to shoot publicity photos. Entrepreneurial as always, Rocco called NBC, who showed up to tape the event—and also provide a protective cover of newsworthiness when the police this time arrived. In an equally risky venture, Rocco smuggled footage of two men cruising in Disneyland for Disneyland Discovery (1969)—which was promptly suppressed by corporate authorities, though it remains viewable at UCLA Film & Television Archive, and represents one more thrilling assertion of gay presence in a distinctly heteronormative “family”-friendly setting.

How to Shoot a Nude on the Freeway (c. 1969)

Some of Rocco’s earliest forays into documentary emanated naturally out of his erotic shorts. Marco of Rio (1969) documents a trip to Brazil, using 16-year-old tour guide Marco Antonio as a window into local and tourist beefcake scenes, while that same year The Groovy Guy records a contest at a gay bar. Rocco’s opening narration, typical of the personable, upbeat demeanor he had developed during his years in the entertainment industry, calls Los Angeles the “capital city of the west, with millions of happy people throughout,” and as if to prove it, another 1969 short documentary, A Man and His Dream, highlights the Reverend Troy Perry, founder of the gay-oriented Metropolitan Community Church and a crucial figure in LGBT religious history. True to form, Rocco emphasizes the positive, downplaying the adversity Perry faced in favor of an idyllic vision of his life. All of the happiness might seem at a four-decade remove blithe or apolitical, but in contrast to the demeaning and insulting images perpetrated by the mass media and bigoted authorities (including psychologists, who considered homosexuality pathological until 1973) at the time, its very pride and simplicity stood as stark rejoinder.

By 1970, however, a grittier and more explicitly oppositional politics began to appear in Rocco’s nonfiction films. His omnibus Mondo Rocco that year combined both erotic shorts (such as The Luckiest Cat in Town, featuring naked men playing with the titular feline, quite charmingly) and his increasingly sophisticated documentaries, including the aforementioned Meat Market Arrest. Homosexuals on the March showed a rally for consenting-adults legislation that would decriminalize homosexual activity. It took another five years for California to pass it, but Rocco captures an emboldened, multi-racial, multi-generational movement, whose activists sport interlocking arms and slogans like “oral can be moral” (another, from Sign of Protest: “Give me sex or give me death”). Almost no other press showed up to cover the rally—or the subsequent motorcade down Hollywood Boulevard also included in the film, as gay activists sing “We Shall Overcome.” In the middle of it, Rocco gets pulled over for standing in a car with his camera—and naturally, keeps shooting.

Promotional material for the Park Theatre. Image courtesy of Pat Rocco.

If 1970 was a banner year for Rocco, 1971 was such for representations of gay life: the year hardcore broke. Wakefield Poole’s Boys in the Sand opened in December of that year, with Fred Halsted’s L.A. Plays Itself following a few months later, and Rocco’s romantic visions would soon be displaced by the ethos of maximum graphic exposure, which he did not embrace for his own work. As hardcore prospered, he followed his muse, spending years and most of his personal savings on Drifter (also known as Two-Way Drift, completed in 1975), a feature-length film again written by and starring Joe Adair, reprising his favorite role as an ambivalent hustler. The film won positive commentary in outlets from Gaytimes to the Hollywood Reporter, but Rocco was unable to secure broader distribution, and it never received wide attention. Today a lost film to all but the archival researcher, Drifter deserves a belated release, with local scenery that would make the better-funded New Hollywood location fetishists jealous.

After the next year’s Gay Pride documentary We Were There (also an unsung and sadly non-circulating treasure that preserves the texture of gay life several years after Stonewall and just before Anita Bryant’s homophobic Save Our Children crusade ushered in the forty-year Republican assault on equality), Rocco turned to local gay politics in Los Angeles, ran an LGBT homeless shelter, and ultimately moved to Hawaii, where he ran another movie theater and recorded more music, among other pursuits. His films continue to await a full rediscovery—even as they still demand, as his early short insisted, Hey Look Me Over.

Essay reproduced with the permission of the author.

This piece was previously published in Free to Love: The Cinema of the Sexual Revolution (2014), ed. Jesse Pires, by International House Philadelphia.

Notes

1. The closest comparison might be William E. Jones’s Tearoom (2007), which recovers police surveillance footage of restroom cruising in 1960s Mansfield, Ohio.

2. See Thomas Waugh, Hard to Imagine: Gay Male Eroticism in Photography and Film Before Stonewall (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996), 270; Jeffrey Escoffier, Bigger Than Life: The History of Gay Porn Cinema from Beefcake to Hardcore (Philadelphia: Running Dog Press, 2009), 50-57; John Burger, One-Handed Histories: The Eroto-Politics of Gay Male Video Pornography (New York: Harrington Park Press, 1995), 14; Richard Dyer, Now You See It: Studies in Lesbian and Gay Film (New York: Routledge, 1990); David James, The Most Typical Avant-Garde: History and Geography of Minor Cinemas in Los Angeles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 371-372. Efforts to recuperate Rocco include Whitney Strub, "Mondo Rocco: Mapping Gay Los Angeles Sexual Geography in the Late-1960s Films of Pat Rocco." Radical History Review 2012, no. 113 (2012): 13-34, and Brian Wuest, “Defining Homosexual Love Stories: Reconsidering the History of Pat Rocco’s All-Male Films at the Park Theatre” (2012).

3. Rocco biographical material based on: Contract with Hal Roach Studios, 16 April 1956, box 1, folder 1, Pat Rocco Papers, ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, Los Angeles; Park Theatre Special Notice, January 1961, box 17, folder 8, ibid.; see also Rocco Papers finding aid (http://www.oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3k4025zg/); Paul Siebenand, , "The Beginnings of Gay Cinema in Los Angeles: The Industry and Its Audience" (Ph.D. diss., University of Southern California, 1975); Rocco interview with Jim Kepner, 27 April 1983 (video at UCLA Film & Television Archive, transcript at http://www.cinema.ucla.edu/sites/default/files/Rocco.pdf); author discussions with Pat Rocco, February 2011 and August 2013.

4. On Polak, see Marc Stein, City of Sisterly and Brotherly Loves: Lesbian and Gay Philadelphia, 1945-1972 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2004)

5. David Johnson, "Physique Pioneers: The Politics of 1960s Gay Consumer Culture." Journal of Social History 43, no. 4 (2010): 867-892

6. Bizarre Productions, Catalo #25 (1969), box 4, folder 1, Pat Rocco Papers

7. Park Theatre flyer, summer 1968, box 5, folder 8, Pat Rocco Papers

8. Somebody review, Variety, clipping, box 6, folder 5, Rocco Papers

9. Jim Kepner, “The Films of Pat Rocco,” Tangents, Feb/Apr 1969, 27-30

Learn More

Discover the Pat Rocco Collection at UCLA, which features his gay erotic shorts, features, documentaries and home movies, approximately 700 items.

Read an extensive oral history with Pat Rocco from 1983.

Search the Pat Rocco Papers at the ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, which include photographs, scripts and other documents related to Rocco's career.

To report problems, broken links, or comment on the website, please contact support

Copyright © 2025 UCLA Film & Television Archive. All Rights Reserved

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation